A lighthouse with a first-person voice

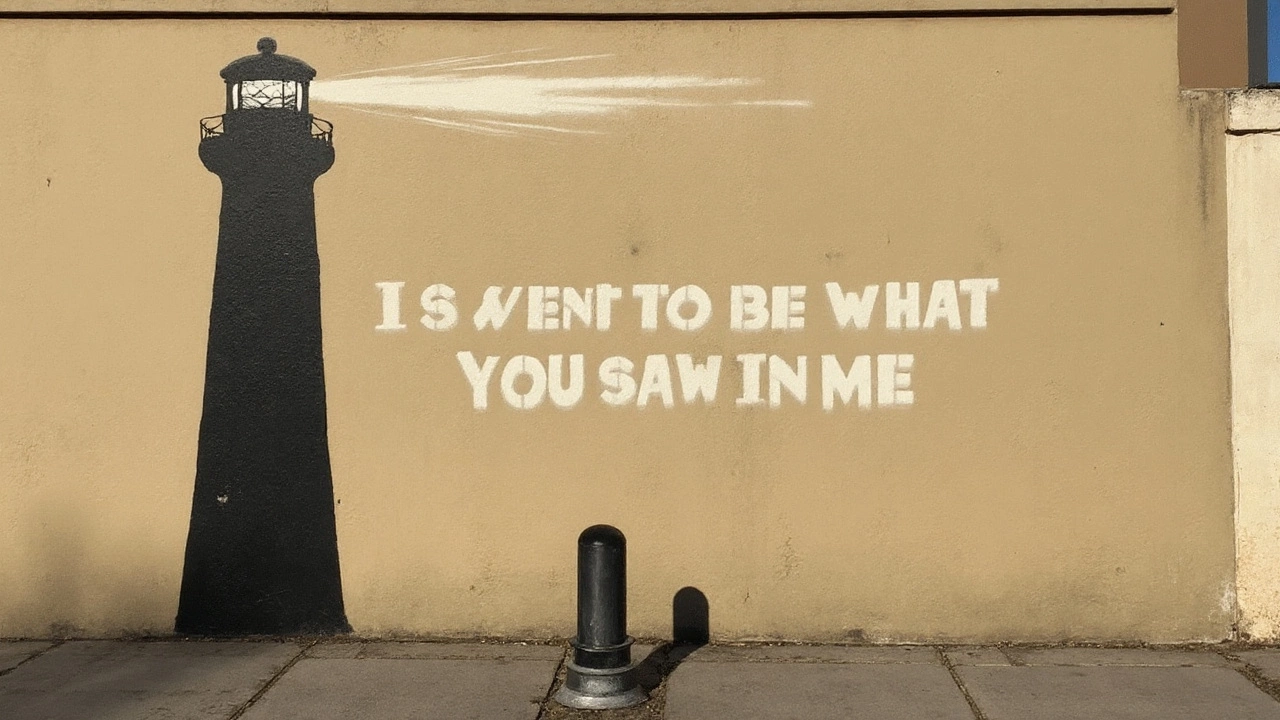

Banksy went quiet for five months, then reappeared with a single sentence that feels like a confession: “I want to be what you saw in me.” He put those words inside a crisp beam of light thrown from a weathered lighthouse, posted the image without a caption, and let the internet go to work. The piece sits on a beige wall in Marseille, France, but the way it was unveiled — secretive, frictionless, maddeningly Banksy — turned a local wall into a global puzzle and a mirror for anyone who’s ever wrestled with identity.

The illusion is clever even by his standards. A stubby metal street bollard nearby throws a real shadow. Banksy painted the lighthouse right where that shadow falls, so the bollard’s dark silhouette appears to sprout into the tower’s base. It’s the sort of site-specific trick he’s honed for years: take what the street gives you — a curb, a crack, a signpost — and turn it into the engine of the image. Here, that sleight of hand makes the beam feel earned, not pasted on. You don’t just look at the mural; you discover it.

What jumps out is tone. Banksy has made a career out of barbs — walls about war, borders, class, the surveillance state. This time, the language turns inward. The line in the beam uses first person — his first public mural to do that — and it reads like a whisper: a love note, a plea, a dare. Is it addressed to a partner, to the public, to the ideal of “Banksy” that millions project onto him? He isn’t saying. That silence is the point. His best work gives you a stage and trusts you to fill it.

Fans mapped meaning fast. Some heard echoes of a country ballad, others a fragment of self-reckoning, the kind you write at 3 a.m. when you’re trying to square who you are with who people think you are. The line is simple and universal enough to land in a hundred different lives. That’s why it hit harder than a slogan. It leaves room.

The craft does plenty of talking. The beam is laser-clean against the wall’s matte texture, a stencil job that demands a steady hand and a plan. The lighthouse itself is scuffed just enough to feel weathered — a structure that’s done its time in storms. That weathering matters. The whole thing becomes a metaphor about endurance: how we hold steady for others, how we learn to live up to the light they think we throw.

He’s played this game with the street before. In Nottingham in 2020, a girl hula-hooped with a bike tire next to an actual wheel chained to a post. In New Orleans in 2008, he framed storm-scarred walls with imagery that made the damage read like part of the composition. This Marseille piece is in that lineage — a reminder that the strongest Banksy works don’t sit on a wall; they fuse with it.

Instagram’s reaction was immediate and almost tender. Compared to the usual roar, this drop felt quieter, more interior. People weren’t arguing policy; they were swapping stories about being seen and trying to live up to it. That shift alone says something about where the artist’s head might be — or at least where he wants ours to go.

The hunt, the city, and the subtext

When the image went up on May 30, he didn’t name the place. He never has to. Within hours, the crowd-sourced investigation kicked off: screen-grabs, street furniture archives, anyone with a good eye for European bollards. Initial guesses landed in Le Panier, the gritty, mural-studded district north of Marseille’s port. The real breakthrough came when viewers clocked a distinctive clue — those short, lighthouse-shaped bollards you see near Marseille’s beaches and promenades. That detail turned a wild search into a grid.

BBC Verify ran the geometry. Using Google Street View and the architectural fingerprints in the photo — the wall’s beige render, the height of window grilles, the angle of the sidewalk — the team confirmed the spot on Rue Félix Frégier, in the 7th arrondissement near Catalans Beach. That’s classic Banksy: choose a place that already hums with metaphor. You can feel the sea from that street. You know exactly why a lighthouse belongs there.

Key details that cracked the map:

- The squat, lighthouse-shaped metal bollards common to that stretch near Catalans.

- The pale beige facade and weathered mortar lines matching Street View frames.

- Window bars and shutter patterns consistent with mid-20th-century Marseille builds.

- The slope of the pavement and curb height aligning with the posted image.

Marseille — France’s second city, ancient port, gateway to the Mediterranean — is no passive backdrop. Lighthouses are built for places like this, where traffic and weather and human ambition collide. The city carries that tension in its bones: rough at the edges, generous at heart, unafraid of contradictions. You can read the mural as a portrait of Marseille itself: a place asked to guide ships through mess and fog, while trying to live up to the stories told about it.

The timing isn’t accidental either. Two major Banksy exhibitions opened in southern France just as the mural surfaced, and while he doesn’t endorse the commercial machine around his name, he has a knack for stealing the spotlight back with a single wall. That judo move — let the shows draw attention, then drop a free, un-ticketed piece on a city street — reframes the conversation around access. You don’t need a wristband to be part of this one.

Critics split quickly. One camp wanted a firebrand — a border piece, a housing jab, a war indictment — and saw the lighthouse as thin gruel. Another camp called it growth: an artist known for public outrage trying something more human-scale, a quieter courage. The disagreement is healthy. When a public artist changes register, it’s risky. The work has to earn the soft voice. Here, the staging, the line, and the street-level illusion do a lot of the heavy lifting.

The phrase itself begs a harder look. “I want to be what you saw in me” reads like a reversal of the usual street-art stance. Instead of telling power what it is, the speaker asks to live up to someone else’s faith. That flips the power dynamic. It also brushes against the weirdness of fame: the anonymous artist who can’t control what “Banksy” means to the world trying, maybe, to meet that myth halfway.

Authentication is its own subplot. As of now, there’s no public note from Pest Control, the artist’s verification service. That’s normal; it often arrives later, if at all, especially for works designed to live and die in public space. Without a certificate, the mural’s market life is basically zero — and that’s the design. Street pieces aren’t meant to be sliced off and sold, though people try. The absence of paperwork keeps the wall where it belongs: for neighbors, passersby, and the occasional pilgrim with a phone camera.

That leaves preservation to the locals. Marseille’s salt air, summer crowds, and the simple physics of a well-traveled corner all threaten the paint. City crews and building owners face a familiar dilemma: protect the work with plexiglass or varnish and risk changing its feel, or leave it exposed and let time, weather, and taggers have their say. Other Banksy walls have been boxed up, relocated, or stripped by thieves in the past, and every one of those choices turns into a referendum on what street art should be — living and ephemeral, or museum-ready and frozen.

The economy stirs around a piece like this. Coffee shops nearby will see the bump. Cab drivers will know the shortcut. Tourists will triangulate the spot between a beach dip and a bowl of bouillabaisse. And residents will do what residents always do: negotiate the line between pride in a local landmark and the hassle of strangers peering into their windows for the perfect shot. The mural makes the block famous and a little fragile at the same time.

For the art world, the shift to first person matters. Banksy’s catalog is crowded with declarations and indictments; this one feels like a self-audit. You could map a line from “Girl with Balloon” — faith and loss compressed into a single floating circle — to this beam of light, which pins down the opposite feeling: the weight of being believed in. If the earlier emblem was about letting go, this one is about stepping up.

There’s also the politics of placement. Even when the text is personal, dropping a work in a busy Mediterranean port is never neutral. Marseille absorbs migrants, money, tourists, tension — a crossroads city that bears Europe’s contradictions on its streets. A lighthouse in that context doesn’t just guide ships. It asks who gets the light and who’s left in the dark. Banksy doesn’t spell that out here, but the site whispers it anyway.

Visually, the mural’s restraint is key. It avoids the temptation to add characters, jokes, or secondary props. The whole scene centers on geometry — a triangular beam, a vertical tower, a rounded bollard. That discipline gives the line in the light room to breathe. You can read the sentence in ten seconds or stand there for ten minutes, watching how the beam reads differently as the sun shifts across the wall.

It’s telling that the location wasn’t cracked by a single paparazzi shot, but by people who know how cities look — the way a Mediterranean curb chips, the shape of municipal hardware, the rhythm of windows along a block. That collective way of seeing mirrors how the piece works. The mural isn’t just an image; it’s a prompt to look harder at ordinary infrastructure. Once you’ve seen a lighthouse grow out of a bollard’s shadow, it’s hard to unsee the possibilities on every street.

Even the wording feels engineered for longevity. Instead of a topical jab that ages with the week’s news, the line is evergreen, portable, available to anyone who needs it. That doesn’t mean he’s abandoning politics. It means he’s flexing a different muscle — the one that builds work you can carry into your day long after you’ve archived the post.

None of this lands without the old trust game between Banksy and his audience. He drops an image. We do the legwork — argue, search, verify, guard. In Marseille, that pact held. BBC Verify’s Street View sleuthing turned speculation into fact. Instagram became a slow-reading club instead of a flame war. And a quiet corner on Rue Félix Frégier, a short walk from Catalans Beach, became a place where you can test a sentence against your own life.

The phrase keeps circling back to the human scale: mentors, friends, partners — the people who saw something in us before we did. Art can’t give you that, but it can remind you to try. That’s the soft radicalism of this wall. It doesn’t shout at power. It asks a harder question: can you become the person someone else already believes you are?

What happens next will likely follow the familiar arc. Pilgrims will come. The city will decide how (or whether) to shield the paint. The piece will acquire stickers, scratches, and stories. Maybe it will survive a summer; maybe it won’t. Either way, the image has already done its work. It turned Marseille’s street furniture into a lighthouse and turned a global audience into detectives and diarists for a weekend. That’s not a small feat for a few layers of spray paint and a line of text.

Call it a course correction, not a retreat. The Banksy lighthouse mural is still about public life, just at the scale of a sentence. It stakes out a territory between protest and confession, between staging and sincerity. If the artist keeps walking this edge, expect fewer punchlines and more lines that linger. And expect more walls that don’t just hang images — they switch the street back on.

- Poplular Tags

- Banksy lighthouse mural

- Marseille street art

- BBC Verify

- Pest Control